How We Can Advance Support for Racial Equity and Racial Justice Funding

By: Lori Villarosa, Founder and Executive Director, Philanthropic Initiative for Racial Equity. This piece was originally published by PEAK Grantmaking on February 1, 2022.

Grants management professionals are strategically positioned to influence a funder’s racial equity and racial justice funding. But in three decades of working in and with foundations, I have consistently seen a pattern where people serving in these roles are excluded from these conversations as a matter of institutional habit. As a result, there is a lack of understanding across the field about how the work of grants management directly relates to advancing racial equity and justice. Even when they are included, the scope of their influence can oftentimes be limited to paperwork, reporting, and only the most technical aspects of the grantmaking process. And yet, they also have the ability to shift what is and isn’t funded, understand what funder pushback might arise, and how grants are understood and reported.

But before I get into how grants managers can impact racial equity and racial justice grantmaking, it’s important to first define these frequently conflated terms and then examine the current racial equity and racial justice landscape.

Racial equity and racial justice defined

Long-standing tensions driven by unequal power dynamics have shaped debates over how racial equity and racial justice are defined and who does the defining, and there has often been little shared understanding of these terms across the philanthropic field. In our work with foundations and movement leaders, we at the Philanthropic Initiative for Racial Equity (PRE) have seen these tension points manifested within hundreds of foundations. But through our work, we also have the benefit of lessons from movement leaders and change agents, and these have inspired some recommendations that we think will help grants management professionals strengthen their own roles in advancing racial justice work.

Over the past three years, organizers for racial justice and racial equity have called for more precise definitions of those terms, in part reacting to the conflation of equity with diversity and inclusion work. That conflation has muddied the distinction between aiming for change within existing systems and aiming to transform those systems as a whole.

Funding with a racial equity lens has four key features:

- Analyzes data and information about race and ethnicity

- Understands disparities and the reasons they exist

- Looks at structural, root causes of problems

- Names race explicitly when talking about problems and solutions

Racial equity focuses on the prevention of harm and the redistribution of benefits within existing systems. Racial equity projects don’t usually attempt to fundamentally transform the systems that generate suffering, but they do address the unfair distribution of pain. Ensuring that as many people of color as possible have collective access to the systems that produce education, employment, housing, and a clean environment is vital.

Racial justice funding encompasses the above features, but adds four more critical elements:

- Understands and acknowledges racial history

- Creates a shared, affirmative vision of a fair and inclusive society

- Focuses explicitly on building civic, cultural, economic, and political power by those most impacted

- Emphasizes transformative solutions that impact multiple systems

Racial justice adds dimensions of power building and setting transformative goals, and explicitly seeks to generate enough power among disenfranchised people to change the fundamental rules of society. Power building includes recruitment, leadership development, people-oriented and people-guided education, alliance building, strategic communications, and the deployment of a variety of pressure tactics, from protests to lawsuits. To change the fundamental rules means that a core dynamic of the system is fixed, added, or removed, shifting the balance of power between the community and key institutions such as government and business. Power building can even include providing social services or support for the arts—two sectors traditionally separated from civic power in philanthropy—if they are clearly and effectively attached to racial justice goals and strategies.

These distinctions are not intended to imply a rigid dichotomy where organizations take one or the other approach. In a resilient ecosystem, leaders operating in a web of self-determining organizations can (and often do) sequence and connect racial equity and racial justice efforts. For example, health equity strategies can distribute vaccine access more fairly (equity) while organizers also campaign for universal health care (justice). A group can raise money to pay bail to reduce harm (equity) while pressing legislators to outlaw the cash bail system (justice). People can advocate for the denial of permits for polluting industries in communities of color (equity) to build a base for future campaigns that replace polluting industries with sustainable ones (justice).

The closer to the ground one gets, the more likely that many groups will be doing both equity and justice work through varied activities and programs. Sometimes, this ecosystem is literally saving people’s lives so they can fight another day.

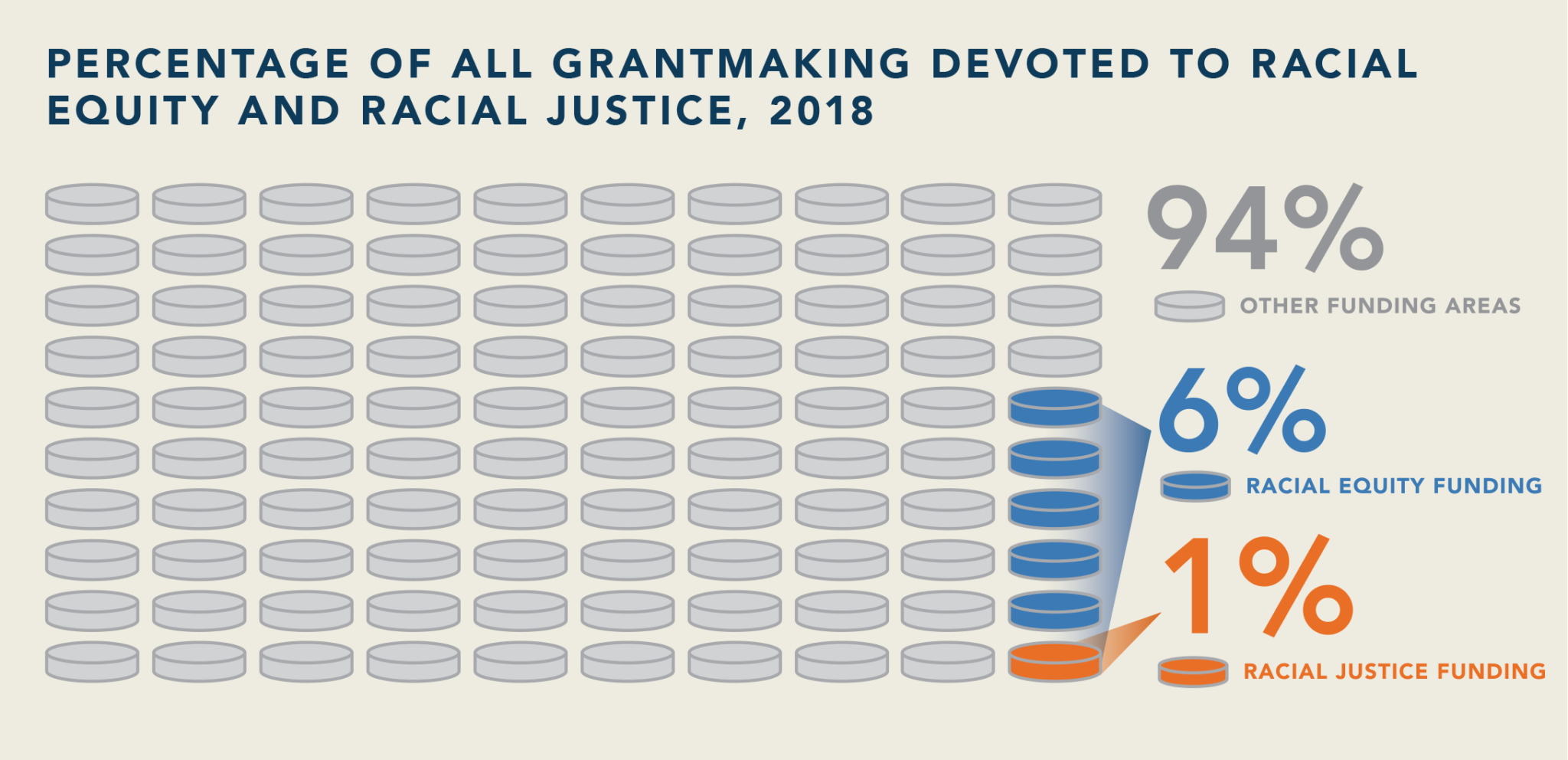

But here is a crucial point: In the absence of power building, racial equity efforts will always have to negotiate within the limitations of current systems. PRE’s latest report, Mismatched: Philanthropy’s Response to the Call for Racial Justice, presents the most comprehensive assessment of racial equity and racial justice funding to date and is unique in that it clearly categorizes and examines funding across these two categories. In a detailed analysis of grantmaking from 2015–2018 and preliminary analysis of funding in 2020, we found that investment in racial justice is consistently a much smaller portion of philanthropic dollars compared to funding for the much broader concept of racial equity. In 2018, the last year for which fully complete grants data were available, only 6 percent of philanthropic dollars supported racial equity work and only 1 percent supported racial justice work.

Dynamics that can hinder or ease racial justice grantmaking

PRE and our many peers advancing racial justice work have long conveyed the critical importance of leaders who understand the issues by virtue of their close proximity to the challenges. This requisite level of proximity can only be achieved through long-term, authentic, and trust-based relationships. Unfortunately, the need to foster these types of relationships are undermined by our implicit biases and the inequitable ways in which our culture frames certain social narratives. It’s these dynamics that give implicit permission to funders to put up barriers and create distance between themselves and grant partners—all under the guise that they are being objective in their decision-making processes. Grants management professionals can leverage their positions to challenge these structures, and they can also mediate between funders and current and potential grant partners, and identify and implement practices that narrow the power gap between funders and grantees.

With that in mind, here are three ways in which grants management professionals can reimagine the core functions of their roles to better support racial justice funding.

1. Identify the why in data management

One of the key takeaways from the research that formed the basis for Mismatched is that philanthropy must require and produce precise data, starting with clear and standard definitions of categories. Without this new standard for data, funders lack the information needed to direct the greater share of support to those doing racial justice work closest to the ground

Grants management professionals collect a huge cache of information, but do they use it in a way that increases funder accountability and transparency in decision-making? And are they committed to acting as change agents for racial justice, collecting the quality and volume of data that could better reveal patterns of racial and ethnic disparities? Are they asking grant applicants doing racial justice work what they need to grow their movements and their impact?

Be intentional about funding racial justice work and reach out to organizations engaged in it. Seek grantee recommendations outside of your usual circles. Support collaborative projects as well as individual grantees. And remove barriers to effective funding that are particularly onerous for grassroots community groups.

2. Ease the burden on grant applicants

A racial justice lens sees time as a key resource and seeks to provide as much of that resource as possible to grantees, rather than extract it through excessive scrutiny or lack of preparation. Typically, a foundation has more flexibility to shift practice than a grantee will have to shift workloads to manage fundraising.

Mounds of research confirm best practices that support grantee stability and growth as well as constructive, trusting relationships between grantees and funders. General support, multiyear funding, a streamlined process, and reasonable reporting requirements are good for all groups. But organizations of color and those tackling racial justice can be particularly harmed by the lack of these best practices because they are often deeply and disproportionately under-resourced. In choosing their own practices, foundations should accept an appropriate portion of the burden for the work required to make a grant.

This includes

- offering application support (e.g., a webinar that explains how the application process works) and adequate preparation time;

- exploring the option to adopt a common application with similar foundations, limiting questions to those required for grant decisions, and being open to having a conversation with grant partners in place of a written proposal or report;

- in project grants, providing at least 25 percent for infrastructure instead of the typical 10–15 percent;

- limiting site visits and, when they are necessary, cover costs for staff, lunch, and other common courtesies; and

- eliminating convenings or collaboration as conditions for funding.

3. Reexamine the concept of risk

One of the key ways grants managers can impact racial justice grantmaking is in relationship to assessment of risk and compliance. I have seen so many foundations whose language around prohibition of advocacy is so much stronger than it needs to be by IRS rules and instead often ties to overly cautious frames by senior leaders or those within the compliance area, such as legal counsel. But the overreaction to perceived risks can deter program staff and grant applicants alike from advancing or explicitly naming efforts that are fundamentally about building power and impacting systems in ways that are critical to real racial justice work. Even more problematically when Black-, Latinx-, Asian American and Pacific Islander-, and Indigenous-led organizations that are historically underfunded are deterred from seeking support for the power-building advocacy efforts that are so needed for racial justice work and are perfectly legal yet explicitly or implicitly discouraged by harsh legalese of grant applications or grant acceptance letters.

But what if the conversation within a foundation shifted and instead focused on the risk of not supporting the most effective justice efforts because of this unwillingness to invest in advocacy? And by extension, what are dangers of perpetuating inequities within the nonprofit structure, of potentially supporting strategies that are too disconnected from community-identified and preferred solutions?

Everyone in philanthropy can potentially play a role in supporting transformative racial justice work. But to unlock that potential, each person needs to apply racial equity and racial justice lenses to all aspects of their work. And grants professionals can be a driving force by both shifting practice and ensuring that the organization is impactfully looking at its work through both lenses.