Fear, Hope, and Hunger: Inside the Crisis at the Southern Border

By Alexandra Rojas, Senior Advisor, Tides

Earlier this month, I had the opportunity to see firsthand the horrid and inhumane living conditions in which the migrants at our Southern Border find themselves. I joined a delegation led by the Center for Democracy in the Americas and National Immigration Forum (NIF) that traveled to Honduras, Juarez, and El Paso, where we met with leaders who are living and breathing the immigration crisis on a daily basis. I was joined by 15 other individuals from the philanthropic, law enforcement, and religious communities. Together, we sought counsel from public and private sector officials, journalists, and NGOs providing direct service. Ultimately, we sought answers: What is happening on the ground? What are the needs? What can we do to help?

The Court and The System

We spent the first leg of the trip in Honduras, but the emotional weight of this experience didn’t fully hit me until we traveled between El Paso, Texas and Juárez, Mexico. The rawness of the experience was surreal, as if I had landed in The Twilight Zone and was traveling through two different yet similar time periods.

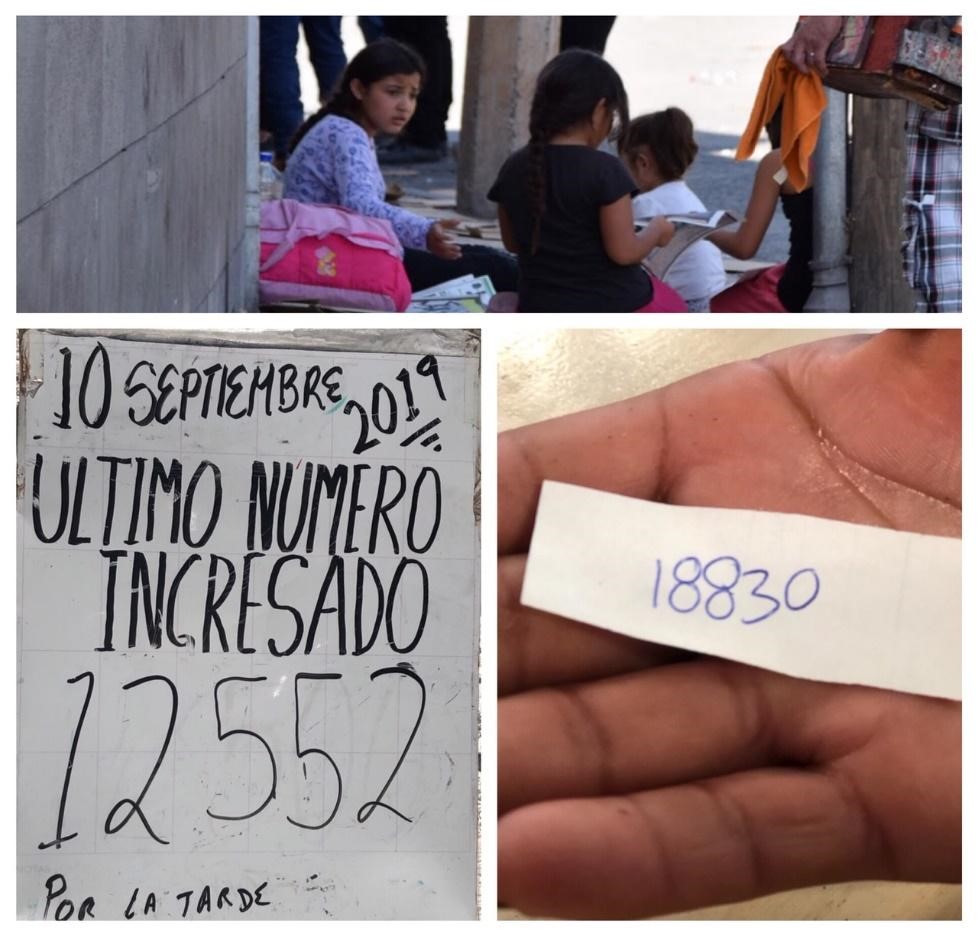

In Juárez, I witnessed fear, hope, and hunger—not just for food, but for information, empathy, and basic human decency. We arrived on the same day the U.S. Supreme Court chose to side with the Trump administration to ban most Central American migrants from seeking asylum in the United States while a court case wound its way through the system. No one was clear on what the process would be like under the new policy. Our only point of reference was a metering system that tracked the order in which an asylum-seeker could go in front of a judge for a first of many appointments. The last number admitted to the US had stopped two days earlier, on September 10th, at number #12,552.

On the day of our arrival, September 13th, a soft-spoken man from Honduras was assigned #18,830. Within two days, 6,000+ more people were on the list crowding around a Mexican government representative in Juárez, hoping he would call their number to let them cross into El Paso to make their case for asylum. But, with U.S. Customs and Border Protection in El Paso calling up no more than 3 to 10 asylum seekers per day in recent weeks, disappointment fell upon the asylum-seekers as strongly as the scorching heat outside while they wait days, weeks, months—or more.

Lost in Translation

In El Paso, Hope Border Institute brought us to observe “bond hearings”, not to be confused with asylum hearings. Here, the buildings are ice cold. About five individuals at a time, and sometimes per day, are brought in to plead their case for a chance to reunite with their family in the United States while they wait for their asylum hearing. Each time, the judge recites the same routine speech. Most asylum-speakers do not speak English, and sometimes not even Spanish. Translation services are not always available, but even in the best of circumstances, the quality is poor. If a translator is not available, the case is reset for at least a month.

Some asylees are escaping misery, the war tax (a fee imposed by local criminal gangs and cartels on farmers and small businesses), the erosion of corrupted communities, and an endless drought overwhelming the northern triangle countries of Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador.

Seeker Shelter and Comfort

Back in Juárez, we visited El Buen Pastor—the Good Shepherd—where a retired teacher-turned-Pentacostal pastor, Juan Fierro, transformed his church into a migrant shelter offering two meals each day, a shower, and a floor mat to rest at night while they wait for their number to be called. A space with capacity for 40-60 for Sunday services now houses 85 or so asylum-seekers on any given day. At its peak, as many as 260 people sheltered there. We spoke with many of them, with each story more horrifying than the last.

We spoke with families escaping the cartels that wanted to force their children into a life of crime, siblings targeted by local gangs and physically abused, and a doctor from Uganda whose wife and children were killed because he chose to service LGBTQ community members at his private clinic. As Yanishley Estrada Guerrero, a Cuban former Bank Manager shared with us, "Everyone cries here, even though we try to keep each other’s spirits up, I cry almost every day."

Continuing Developments

Continuing Developments

This week, we learned of the Administration’s new deal allowing US border patrol to deport asylum seekers to Honduras, a nation that The Washington Post notes has “one of the highest murder rates in the world.” Similar deals with El Salvador and Guatemala have already been approved, but the details of these “safe-third country agreements” have not been defined. Meanwhile, migrants are left crowding the streets in Juarez and other ports of entry, praying not to be the target of kidnappers and extortionists, and relying on the good deeds of local faith organizations and what family members can spare.

What Comes Next and What We Can Do

The reality at the border is difficult to comprehend, and my colleagues and I [at that time] often felt helpless during our experience. When in Juárez, we spoke with Linda Rivas, the Executive Director of Las Americas Immigrant Advocacy Center and pro bono attorney, and some of her words stuck with me: “In the eyes of the world, we should be ashamed.” I agree. And there are actions we can take.

We must do better—both domestically and abroad. We need to seek information, and not simply accept the divisive national rhetoric or the social media “us vs. them” stories that are passed around as facts. We have to share our experiences with each other and make an effort to have respectful conversations about sometimes opposing points of view. We have to avoid the extremes on all sides, which threaten to push us further apart and erode our ability to find a humane solution.

Most of all, we need to increase our capacity at the border and integration of services. Earlier this year, the National Immigration Forum looked at the push and pull factors driving migration from Central America. “If we are serious about solving the crisis at our border, we need short-term and long-term solutions that address those push factors, including efforts to counter human smuggling operations, provide aid to Northern Triangle countries to strengthen the integrity of local institutions, and establish in-country relocation areas for the internally displaced,” explained Ali Noorani, Executive Director, NIF.

In whatever capacity we can—with our voice, our vote, our values, and our wallets—we have a moral responsibility to do the work that the US should be doing and stop simply accepting shame as the norm.

Challenging Fear and Standing Up for Humanity

I’m taking a first step by hosting a conversation on October 10th at Uniting US: Challenging Fear and Standing Up for Humanity. I will be joined by leading practitioners to discuss the current immigration narrative and perceptions related to culture, security, and the economy. The goal is to learn about some of the ways peers and changemakers are using these strategies to promote social inclusion and belonging, to galvanize supporters, and to recalibrate our democracy and our values.

Since 2012, Tides has facilitated more than $30 million in grants to support immigrants and refugees in the areas of grassroots civic participation and human rights, and more than half were domestic in scope. As a strategic advisor and facilitator on domestic and international grantmaking, Tides can partner with individuals, groups and institutions to design a grantmaking approach that aligns with your mission and values; conduct due diligence on potential grantees; develop advocacy, civic engagement, and communications campaigns; join existing funding collaboratives; connect you with like-minded donors or organizations like the Center for Democracy in the Americas to help you amplify your thought leadership; and support civic engagement organizations to ensure that our democracy truly reflects all voices.

I refuse to be just a bystander in the face of this crisis. I choose to stand up for the dignity of every human being regardless of immigration status or what side of the border they’re on. To me, that is fundamental to the idea of America. Unite with us to challenge the fear and hatred. Stand with us to protect our shared values.

Images by Melysa Sperber, Director of Policy & Government Relations at Humanity United